Exhibition Design

GD 762b

Spring 2020

« Every writer has only one story to tell, and he has to find a way of telling it until the meaning becomes clearer and clearer, until the story becomes at once more narrow and larger, more and more precise, more and more reverberating. »

—James Baldwin

To my students:

While the future promises us only uncertainty which makes us feel uprooted and disoriented, perhaps we could try fully surrendering to the uncertainty and actively embracing the unknowable. Then we can shift our focus back to what is graspable, what we can control. We can solidify what we already have, recalibrate and redefine our frame of orientation, and plant a seed for eventual efflorescence.

So here is what we will do.

This last assignment is to acknowledge, celebrate, and preserve all the work you have done together in the exhibition design class this semester and to encourage to still explore and apply your own thesis pressed against the exhibition class’ collective thesis. And more importantly, this is how we look toward our uncertain future from a ground that would be made solid by you, and maybe even appreciate the spaciousness of the uncertainty.

Each person will leave something behind—for your show that will happen at some point in the future. It is a note, a brief, a proposal, a set of instructions, a script, a blueprint, a schema, a statement, or any combination of these... in other words, any form of embodiment of your idea, which will be translated into a physical show in the future. There are some conditions to this (I’ll simply call this “document” from here on):

- Suppose somebody else who was not part of the process will execute your idea, solely relying on this document.

- Suppose your document is the only document based on which the show will be realized. Meaning, each document is not a part of a bigger whole. It is one version of the potential reality. Each version should be complete within its own world.

- It should be grounded in the ideas that you have collectively developed, but doesn’t have to be limited to only what has been discussed and agreed upon. What that collective idea is, is really up to your own interpretation. Re-examine the idea if necessary. You are the conceiver and author of this reality.

- It can be as general or specific, as literal or poetic, as comprehensive or selective as you see fit. Your focus can be on defining ideas, sensory qualities, or it can even include specific designs for any parts of the show. It can also be very practical (i.e. the perfect ratio of the reflective paint to water) if you think that’s crucial and meaningful.

- It can take any forms (text, image, moving image, sound... or any other medium). However, how you articulate and externalize the idea should reflect your own interest, thesis, and methodology. This document is your work on every level. It just needs to be in a transmittable form.

- What is important to remember is that you are handing something concrete and finite over to someone else, in order to ensure what is important to you about the show gets heard, considered, and manifested without your presence and direct participation. The document itself is your own expression, but made with profound consideration of the receiver of your document, who is also the realizer of your idea. Knowing it will be decoded with some level of inevitable subjectivity, what will you provide, and how? Thus this is an exercise in speculation, but moreover, an exercise in empathy.

- The document must include your own title of the show.

You know, this show was always going to be about immateriality, or rather, dematerialization of work, and documentation and circulation of ideas, one way or another. Think about it.

We will do quick individual check-ins on April 23 during our usual class time. Your final document should be submitted to yeju.choi@yale.edu by May 6. We will have one final class meeting during the week of May 11 (we should talk about what day would be good for everyone) when you see everyone’s document and give comments—before we put everything in a box(or, a folder), and away, for now.

« Talk of unstructured content or an unconceptualized given or a substratum without properties is self-defeating; for the talk imposes structure, conceptualizes, ascribes properties. Although conception without perception is merely empty, perception without conception is blind (totally inoperative). Predicates, pictures, other labels, schemata, survive want of application, but content vanishes without form. We can have words without a world but no world without words or other symbols. »

—Nelson Goodman, Ways of Worldmaking

and again,

« Every writer has only one story to tell, and he has to find a way of telling it until the meaning becomes clearer and clearer, until the story becomes at once more narrow and larger, more and more precise, more and more reverberating. »

—James Baldwin

April 12, 2020

YC

Here are some references to inspire you, but do not feel limited by what you see here. Scroll through for fun.

You can actually download a full set of high & low res scans here.

In 1960, Richard Hamilton made an English-translated, typographic version of The Green Box, called The Green Book. (More about this dialogue here.) Here are some parts of the book. (Sorry for the weird cropping due to my haphazard scanning):

I was also thinking about this older piece by Duchamp, Unhappy Readymade, 1919–1920: “The artwork was a wedding present to Duchamp’s newly married sister, and consisted of instructions to go out and buy a geometry book and dangle it by strings from their balcony.”

Seth Siegelaub, “a gallerist, independent curator, publisher, researcher, archivist, collector, and bibliographer, often billed the father of Conceptual Art,” stated on the catalogue of this show: “the exhibition consists of (the ideas communicates in) the catalog; the physical presence (of the work) is supplementary to the catalog.”

You can see the entire publication here.

“This book, also known as One Month, was organized by Seth Siegelaub and took the form of a page-a-day calendar for the month of March 1969. Siegelaub developed the book by assigning each of the 31 invited artists a specific day of the month (and its corresponding page) upon which they would construct a work. These text-based works were then collated and published by Siegelaub, leaving blank the pages assigned to artist who failed to respond.” (Source: Primary Information)

See other publications by Seth Sieglelaub here.

To learn more about Sieglelaub, there’s this comprehensive, Irma Boom-designed catalogue to accompany the show Seth Siegelaub Beyond Conceptual Art at Stedelijk Museum.

From this book (excuse my phone photo... no scanner at home):

which included this project by Douglas Huebler:

which included this project by Douglas Huebler:

Source: MoMA

“This project is part of the first in a series of Seth Siegelaub’s ‘catalogues-as-exhibitions,’ ... Legend has it that several people went to Siegelaub’s apartment showroom at 1100 Madison Avenue, hoping to see an exhibition that had no physical existence part from the catalogue. Even so, interested buyers were offered various ‘artistic documents’ that Siegelaub kept in the apartment. The collector Alan Power paid the stately sum of $2,000 for three of the works listed in the catelogue—Siegelaub’s first big sale; and Raymond Dirks, a stockbroker and patron of the arts, had financed the catalogue in exchange for several artworks (including one listed in the catalogue).” (taken from the aforementioned book, p. 100.)

Siegelaub also published Lawrence Weiner’s Statement.

“After students at Windham College destroyed the site-specific installation he had made there (Staples, Stakes, Twine, Turf) because it blocked their access across the campus lawn, Weiner formulated the famous declaration of intent that would underpin his entire work: ‘1. The artist may construct the piece. 2. The piece may be fabricated. 3. The piece need not be built. Each being equal and consistent with the intent of the artist the decision as to condition rests with the receiver upon the occasion of receivership.’And he went on to create Statements, comprises twenty-four works in the form of texts and organized according to ‘General Statements’ and ‘Specific Statements.’”

“After students at Windham College destroyed the site-specific installation he had made there (Staples, Stakes, Twine, Turf) because it blocked their access across the campus lawn, Weiner formulated the famous declaration of intent that would underpin his entire work: ‘1. The artist may construct the piece. 2. The piece may be fabricated. 3. The piece need not be built. Each being equal and consistent with the intent of the artist the decision as to condition rests with the receiver upon the occasion of receivership.’And he went on to create Statements, comprises twenty-four works in the form of texts and organized according to ‘General Statements’ and ‘Specific Statements.’”

While I’m at it, some spreads from Weiner’s publication Displacement, 1991 (again taken poorly by my phone):

While I’m at it, some spreads from Weiner’s publication Displacement, 1991 (again taken poorly by my phone):

Oh, let’s not forget his piece Gloss white lacquer, sprayed for 2 minutes at 40lb pressure directly on the floor, 1968.

And of course, Sol Lewitt.

And the instruction for the piece:

I found this in the catalogue for the 1978 show at MoMA, which is apparently designed by Sol Lewitt himself. You can download this out-of-print book from the MoMA Archive.

I found this in the catalogue for the 1978 show at MoMA, which is apparently designed by Sol Lewitt himself. You can download this out-of-print book from the MoMA Archive.

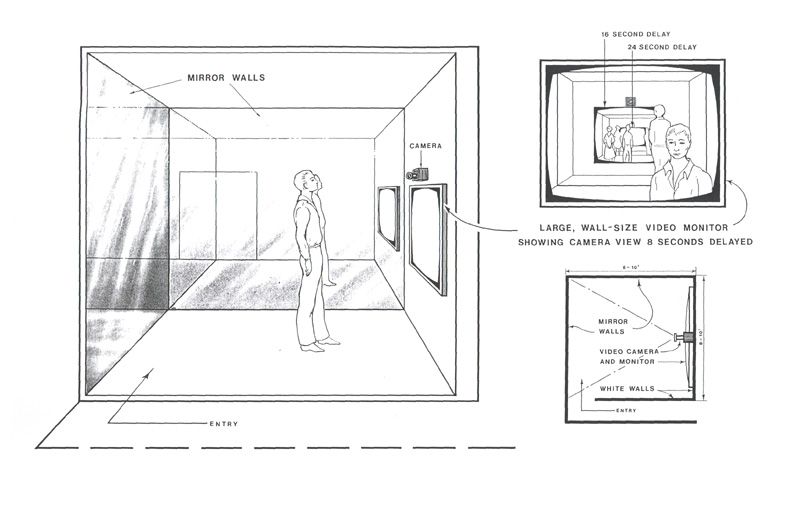

How about Dan Graham’s drawings?

and his texts?

“For Schema (March 1966) Graham used the physical structure and context of printed pages in publications to craft a series of ‘poems.’ Its panels comprise pages of Graham’s contributions to artists’ books, exhibition catalogues, and periodicals or his notes for unpublished texts. These ‘poems’ define the composition and its contextual surroundings, giving shape to an open–ended yet highly defined structure. As Graham described Schema:

It is completely self-referential. Instead of relating to the white cube of the gallery, the work involves the ‘materiality’ of its own self-referring information. As magazine information is disposable, the pages defeated the monetary aura of gallery art and also had the virtue of positioning art in a popular and publicly accessible domain. Placing work in the context of the magazine page allowed it to be read in juxtaposition to art criticism, art reviews, and art magazine reproductions of art objects installed in exhibition spaces.” (from MoMA)

This also appeared as his contribution for Aspen, “the first three-dimensional Magazine in a Box”, no. 5+6 The Minimalism issue, 1967: See here.

While looking at the Aspen magzine, let’s dig deeper. Because... it is amazing.

In no. 8, the Fluxus Issue, 1970–71, edited by Dan Graham,

Yvonne Rainer’s schematic drawings:

Richard Serra’s Lead Shot, a description of a sculptural project:

FYI, you can see and touch the Aspen magazines at Yale Art & Architecture Library (I mean, when we are back in the world). I went to see them when I was a student! They are truly amazing.

A bit more from Fluxus...

Source: MoMA

George Brecht was one of John Cage’s students at the New School for Social Research, where “between 1956 and 1960 Cage influenced a generation of artists who would develop the performance script into an art form and lay the ground for Happenings and Fluxus.” (source: The John Cage Trust)

Yoko Ono was also influenced (her husband—before John Lennon I assume—was in Cage’s class, but she was not).

If you are curious to see how this piece was actualized in 2012: See here.

And a Fluxus bassist, sculptor, painter and collagist Benjamin Patterson:

You can listen to one of his recordings here.

(How are you doing? Are you feeling inspired yet?)

More about Mel Bochner: melbochner.net

John Baldessari’s A Painting That Is Its Own Documentation is “a canvas featuring painted text that tells the story of its own origins and records each subsequent exhibition outing—requires new lettering to be added each time it’s shown.” (from Artsy)

And this is one of Baldessari’s list of “assignments” for his CalArts class, 1970 (read more here and here.

And the Venice Biennale installation of The Probable Trust Registry: The Rules of the Game #1-3: see photos here and here.

Instruction drawings for White Paintings by Robert Rauchenberg:

Also this telegram by Robert Rauchenberg:

Donald Judd’s instruction drawing:

Scaling up...

Cedric Price, “the unconventional and visionary architect best-known for buildings which never saw the light of day,” made a lot of incredible drawings for his speculative projects. See more here, here, and here.

More...

And even more...

... and circling back to what we do: graphic design.

“Imagine this book to be twice as large, with a hardbound cover and gold debossed title, beautiful endpapers, head and tail bands, and a dust cover with a French fold. The inside would have glossy, coated paper throughout. Printed on this paper would be a number of carefully selected full color reproductions of landscape photographs of the Mojave Desert. The photos would have been taken with a field camera holding 8x10 inch negative film. The reproductions would be scanned with the latest high-end scanning device, and printed at 300 lines per inch in five colors with a spot varnish. The tonal qualities and detail of the reproductions would match the originals perfectly. To explain the images and create context, there would be two critical essays by well known critics. And to lend the book credibility it would be published by a New York art book publisher or institute of photography. It would be a beautiful book, indeed. This is not that book (See figures 2-155).”

You can see the entire book here.

Actually, did you know he is the one who founded the magazine and type foundry Émigré? Here is a 1992 Interview with VanderLans, on Émigré and other things.

Talking about Émigré... Look at this spread from Émigré #25: Made in Holland, 1993.

On the left is an interview with Armand Mevis (go to the website if you want to read it), and on the right, Berry Van Gerwen’s drawing somehow connects nicely to everything I showed you above.

While on Mevis and Van Deursen... Here is their contribution for the exhibition Forms of Inquiry, which I mentioned in class a while ago.

Lastly(almost), my special gift to you: a few spreads from Tom Sachs Tea Ceremony Manual which I made in 2016 with Tom Sachs and the Noguchi Museum.

Oh, remember I said I was still waiting for the day when I accidentally encounter my books at a used book store? It actually happened right after I said it at my beloved neighborhood bookstore, Unnameable Books:

OK. If you have made all the way down here, you deserve some Hennessy Youngman:

on Studio Visit

on Studio Visiton Grad School

Read about this project on Net Art Anthology.

I am curious to see what your instructions for the future will be. Take care of yourself. Make yourself a cup of tea.